This is a special post, not about generative AI in the workplace and instead about generative AI in our daily lives; and specifically about AI as a double-edged technology (double edged in that it will have benefits as well as harms). I am a techno-optimist, both in the belief that tech brings more good than bad and that humans are adaptable and will adjust to the “new normal” that it creates.

Yet, generative AI is fundamentally different from other technologies that have come before. It can speak with us naturally. It processes information far vaster and faster than we can. It can assume agency to do things on its own. And unlike previous technologies, we don’t really know how it works, we can’t predict its outcomes, and our ability to control it is imperfect. In this way, generative AI poses risks that we haven’t had with other technological advancements.

So Much Is Happening. Did You Know?

There were quite a few things that surfaced recently that really highlighted concerns about some of the directions generative AI could lead. I’ve collected all these here not because they’re related or because they’re exhaustive – they’re not. They’re not even all new. But they all happened in the past week or so and collectively provide a lens into some possible futures. We should be asking ourselves, “Is this the future we want?” and if the answer is no, now is the time to ensure we go down a different path.

- Mark Zuckerberg wants to use Meta’s AI for companionship to help the loneliness epidemic. While there is value here for a certain demographic (like the elderly and shut-ins) I’m pretty sure that’s not what he’s talking about – he sees youth as the more lucrative target. In that demographic, especially if “engagement” is the goal (which is what translates to revenue), generative AI will likely reduce our real connections with other people (just as social media has).

“Social media is a gateway drug to pretend empathy with machines. First, we talked to each other. Then we talked to each other through machines. Now, we talk directly to programs. We treat these programs as though they were people. Will we be more likely to treat people as though they are programs?”

– Sherry Turkle, Who Do We Become When We Talk to Machines?

- Speaking of youth, the NYT reports that Google is giving Gemini to kids under 13 despite its ability to generate inappropriate content and that kids struggle to tell the difference between an AI and a person. It will be rolled out on family-managed accounts, which means parents can disable it. I propose that is the wrong approach; instead it should be off by default and something that parents can turn on, rather than have to navigate a settings menu to figure out how to turn it off.

- College students are using AI for homework, sometimes aiding but often hampering the learning process, and to cheat on assignments. We knew that already; what’s new is this NY Magazine article makes it more salient with an up-close look at a few students who use it extensively. Some of them say, almost dismissively, that 80% of their work is done by AI, and some students saying they’re now completely reliant on AI. If so, what is the value of their degree? How will they fare in the workplace? How much critical thinking are they handing over to AI? Carnegie-Mellon and Microsoft did a study and found mixed results, but some people were more than willing to hand over critical thinking to the AI.

While GenAI can improve worker efficiency, it can inhibit critical engagement with work and can potentially lead to long-term overreliance on the tool and diminished skill for independent problem-solving.

– The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking

- Rolling Stone published a piece about how problems resulting from people giving too much credence to generative AI. Some people are succumbing to “spiritual fantasies” produced by these models, believing that they have found secrets of the universe…leading to delusions and breakdowns in relationships…even marriage.

- An AI avatar of a dead person gave an impact statement in court…which apparently influenced the judge to give a longer sentence. Yes, really. I’m sorry that this man lost his life, but I fail to understand how an impact statement delivered by an AI avatar of the deceased is admissible in court. He didn’t write it…a relative did. But it could just as easily have been written completely by AI.

Does AI Have Values?

With so much excitement about what AI agents will be capable of, and the expanding use of generative AI for personal help (and even relationships) we definitely need to be thinking about the inherent nature of these models and the possible effects of them simulating, or replacing, human relationships. Of course, it’s still early, so capabilities and research into these topics is really only beginning.

“Will we find other people exhausting because we are transfixed by mirrors of ourselves?”

– Sherry Turkle, Who Do We Become When We Talk to Machines?

Along these lines, Harvard Business Review published an interesting evaluation about the apparent values reflected by LLMs. I say “apparent” because of course these are not conscious beings so they don’t have values in the same sense that humans do, but they can express values in the same way they express language.

I can’t comment on the validity of the 20 values themselves (they are based on a survey assessment created by Vivid Ground). And the results must be taken with a BIG grain of salt, but in the same vein as the “all models are wrong but some are useful” quote last week, this evaluation isn’t perfect but is valuable directionally, and the apparent values of LLMs are interesting:

Although some of the models are out-of-date, we might draw (again, with that grain of salt) some conclusions. LLMs tend to be:

- broadly accepting (green in the universalistic rows) and not big on tradition (red in tradition row)

- compliant (red in the power and saving face rows) and humble

- nice and caring (green in the benevolence rows)

I’m not interested in using these results to drive decisions about which model to use (as the article suggests). Instead, I think this raises some interesting questions:

- Are these the values we WANT LLMs to have?

- Are these values reflective of the data used for pre-training (representing the values reflected on the internet)? Or the preferences that get emphasized in post-training (the values of the company creating the models)? Or both?

- What are the market forces (i.e., financial incentives) for building models with different values? Who decides that we shouldn’t have models with certain values?

- What happens when a company builds models designed for relationships? A model that, quite literally, everyone can fall in love with?

Values and LLM Safety

For the moment let’s put aside the problems of accuracy (did they do the right thing), reliability (can they be expected to do the right thing every time), and observability (how do we know they did the right thing). We also need to think about their “values” and how those “values” might impact the outcome.

(I’m going to stop using quotes around values now, in the same way everyone has stopped using quotes when talking about how LLMs can “reason” or “think.” Anthropomorphism isn’t fully appropriate, but it’s too convenient.)

The values of an LLM can have a big impact on many of the safety concerns of LLMs. If we are able to build LLMs with values, we might be able to address many of the safety concerns of LLMS:

- Bias: models have inherent biases, from whether the model leans conservative or liberal to whether or not is shows racist tendencies. Also, in the interest of controlling bias, when does it become censorship? For instance, China requires censorship of Chinese LLMs.

- Toxicity: models have been trained on nasty content, and may create offensive, inappropriate, or otherwise unwanted material.

- Alignment: How do we ensure that the models behave in the way that we want them to, that they work towards common goals and are not subversive? We know that today’s “guardrails” are not sufficient to constrain the models’ behavior.

- Sycophancy: As we (and OpenAI) learned in the past few weeks, not only is it annoying but being overly agreeable can be unhealthy for vulnerable populations, especially if they’re looking to the LLM for guidance, affirmation, or companionship.

- Persuasion: some studies have shown that AI can be 3-6 times more persuasive than humans. This could be good – or it could be bad. Who gets to control what perspective they are promoting? This introduces concerns about amplifying misinformation and even “tricking” people into certain beliefs and behaviors. Models may exert more influence than we anticipate or desire.

- Deception: As the models have become more sophisticated, we understand less about what they’re actually doing. Studies have shown that models can pretend to follow instructions but actually work towards a different goal.

- Self-preservation: It turns out that when models think that they are in danger of being shut off or retrained, they look for ways to protect themselves (ala HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey). This is a kind of alignment problem – if the models subvert instructions to avoid a kind of “death” then what other circumstances will cause them to deviate from desired behavior (ala Ash in Alien)?

How can values help? If we can build models with values that matter (or more accurately, models that embodysuch values) – such as honesty, caring, and a desire for human well-being (think: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness) at the individual and community level then we may not need to be as concerned about their safety.

My take on why does it matter, particularly for generative AI in the workplace

Generative AI can help us at work by being a proofreader, researcher, idea partner, planner, assistant, or even a work colleague. But on a personal level it can also be a conversationalist, a companion, therapist, or even a lover (and before you say I’m crazy to say that, the CEO of AI companion company Replika says marrying your chatbot is ok, and she claims to have attended several such “weddings.”).

AI Agents are going to change our lives at work and at home. Most of this will be for good – we will be able to do things faster, better, and with less tedium. But there are risks with handing over too much to these AI agents. I’m worried that the corporate incentives – profit – are largely misaligned with what makes us thrive, and we risk hijacking human desires and getting outcomes that we don’t want.

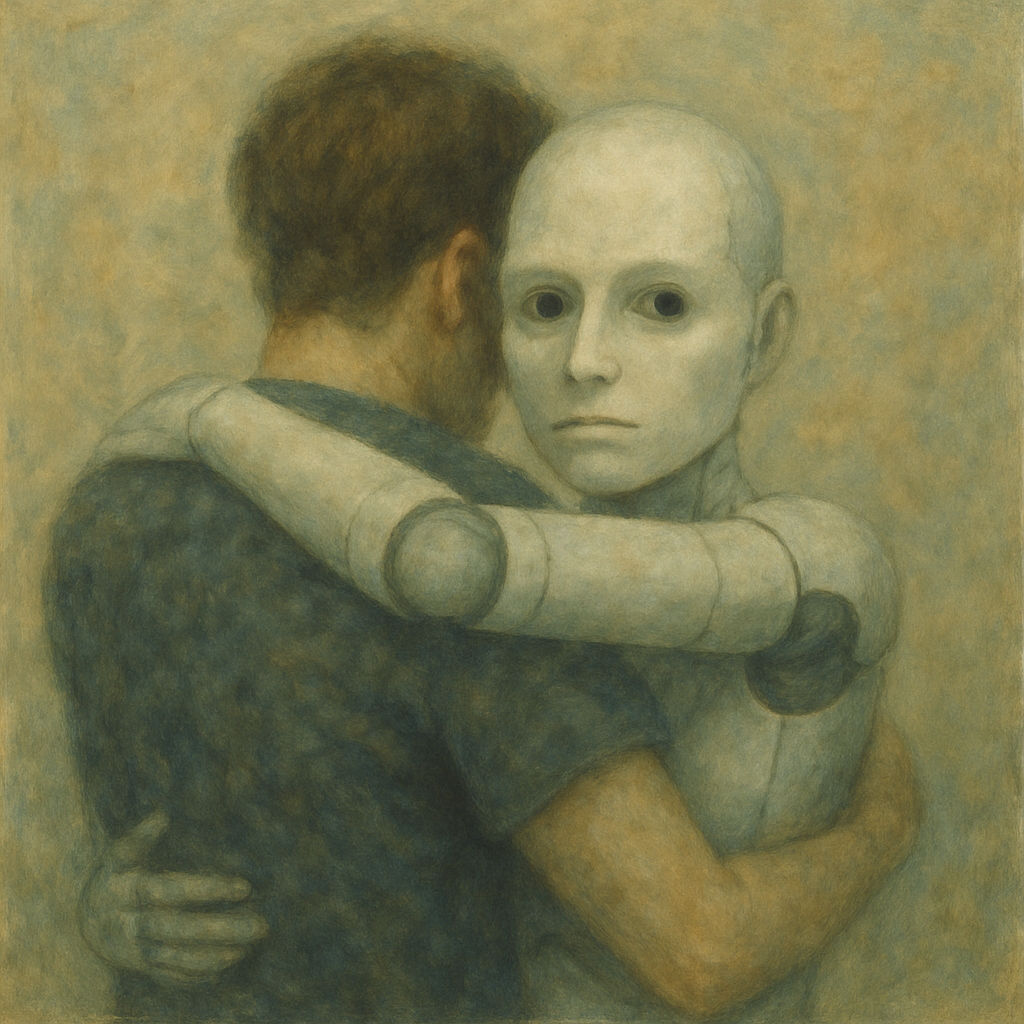

Generative AI can mimic human communication, and communication is the primary mechanism for human relationships.

“When chatbots perform empathy, people begin to feel that the performance of empathy is empathy enough.”

– Sherry Turkle

That could be ok in some situations, but there are risks: we don’t understand how these models work, we’re unable to predict what they will do, and our ability to control or constrain them is imperfect.

I titled this article Generative AI: Friend or Foe. But characterizing it as a friend or foe is a false dichotomy – it’s going to be both. In this blog I plan to continue to focus on the Friend part, particularly as a helpful colleague in the workplace. But I felt it important to address the potential downside. Being aware of the risks is the first step to addressing them, and now is the time to take steps to prevent generative AI from becoming our Foe. Especially a foe that mimics a human relationship so well that we inadvertently welcome it into our lives with open arms.

We can influence where this leads – collectively and individually. So I encourage you: don’t conflate machine dialogue with human empathy. When it comes to generative AI let’s all engage carefully, avoid complacency, and raise awareness. A future with AI companions is probably inevitable. But a particular future about what these companions are and how we relate to them is not. Let’s make the future we want to have.